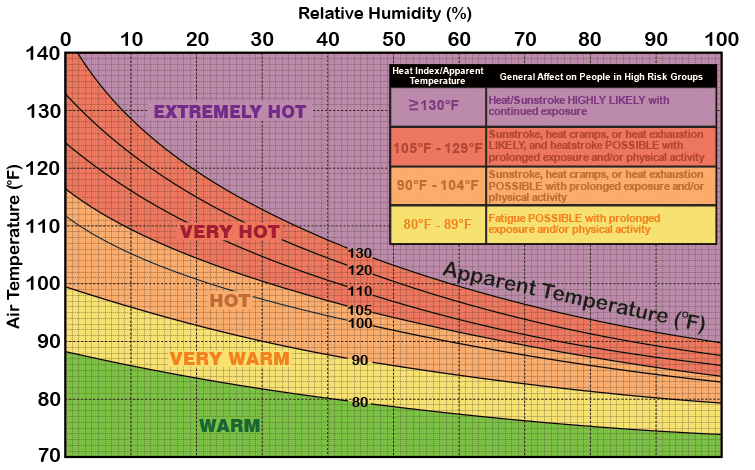

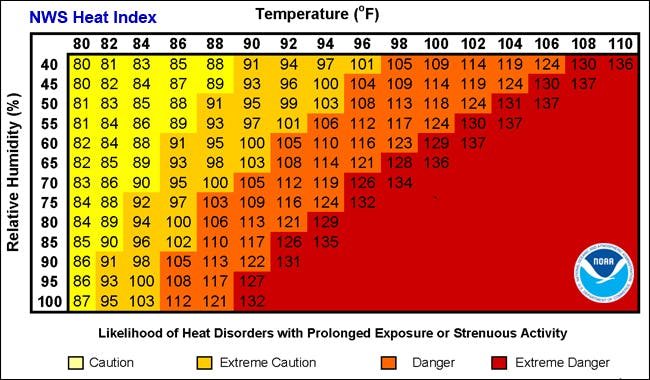

Tucson and Houston are both incredibly hot cities. But strategies for cooling their neighborhoods in the face of record high heat are drastically different. And it is for a simple reason: Tucson is dry, and Houston is humid. And in humid cities the amount of water in the air, the humidity, is just as important as the temperature—especially to human health. When a 92°F day actually “feels like” a 108°F, it means the humidity is making the heat more dangerous to your health.

Humidity during high heat events prevents the natural cooling systems of the human body from operating efficiently, and can be deadly. At least fifteen people died in Houston due to heat-related illness during the summer months in 2023, even without any massive power outages. The effects of heat stress are even more pronounced in children and people over the age of 65. Children have a smaller body mass to surface area—skin—ratio than adults, making them more susceptible to heat. They also breathe faster than adults, making dehydration a bigger threat.

And the humidity in places like Houston, or New Orleans, or Atlanta makes cooling cities more nuanced and challenging than cities in dryer climates like Tucson. Trees cool cities in two main ways. First, they provide shade, intercepting the heat from the sun that is absorbed into the ground surfaces. That is pretty intuitive. The second way they cool the city is perhaps less observable, but equally important. Trees also cool the air through evapotranspiration. By converting the water in their roots into water vapor through their leaves, heat is absorbed from the air.

The challenge in humid climates is that this process also increases the humidity in the air. Which makes us feel hotter, and increases the dangers of heat stress. A recent article in the journal Nature outlines this conundrum. The researchers found that while trees lower the temperature through shading and evapotranspiration, they also increase the humidity in the area. Whether the overall trade off between temperature and humidity is favorable is still unknown, and is likely to depend on local conditions.

How Heat Index chart for areas with high heat but low humidity

Credit:

NWS

Heat Index chart

Credit:

NWS

What it does point to is the fact that addressing climate change through green infrastructure requires a more nuanced approach than simply “greening” everything, especially in humid climates. Trees may actually, in certain site conditions, trap long-wave heat from dissipating from paved surfaces at night, increasing the amount of heat stored at the ground level over the course of a heat wave. In dry climates, more trees are typically better, as evapotranspiration is an incredibly effective cooling device.

The irony is that in the places where evaporative cooling from trees is the most effective, such as dry cities like Tucson, water is often the most scarce; while in the humid cities with lots of water, trees and vegetative strategies may raise the humidity—and the heat stress. This is not to say trees aren’t great. Here in New Orleans, we have so few trees, we need to plant as many trees as possible—especially in places where they can cool people’s houses and neighborhoods. But the situation in humid climates is complex. And understanding the complexity, and how to design for it, is the beginning of dealing with one of the most pressing issues of our time.